Road to Sphere #3: MCM and SCELBI!

The MCM/70 and SCELBI computers. Plus, Ben's on a podcast!

The crowdfunding campaign for Go Computer Now! is a bit more than halfway over, and I want to thank those of you on this list so much for your support. If you haven’t had a chance to check it out yet, please do!

A quick note to this audience that Sean Haas of the rather wonderful Advent of Computing podcast kindly had me on as a guest talking about Sphere for an episode that was posted this morning. We got into, among other things, the 1960s TRAC language. I also just encourage you to check out Advent of Computing. Sean takes the sort of thoughtful, forensic approach to all of his work that really resonates with me. (And my thanks to Andrew S. for recommending this to me!)

But! With so much Sphere content in the campaign, I figured why not do a mid-campaign palette cleanser to dive into some more pre-Sphere systems that are worth being curious about! Once again, this is material that is not in the book because my editor was wise enough to counsel me against it. Available here on the newsletter only! I love these other histories and spent some real time getting to know these stories so that I could distill them like this. Enjoy.

Micro Computer Machines

“I was always more attracted to the things they said could not be done.”

– Mers Kutt, founder, Micro Computer Machines

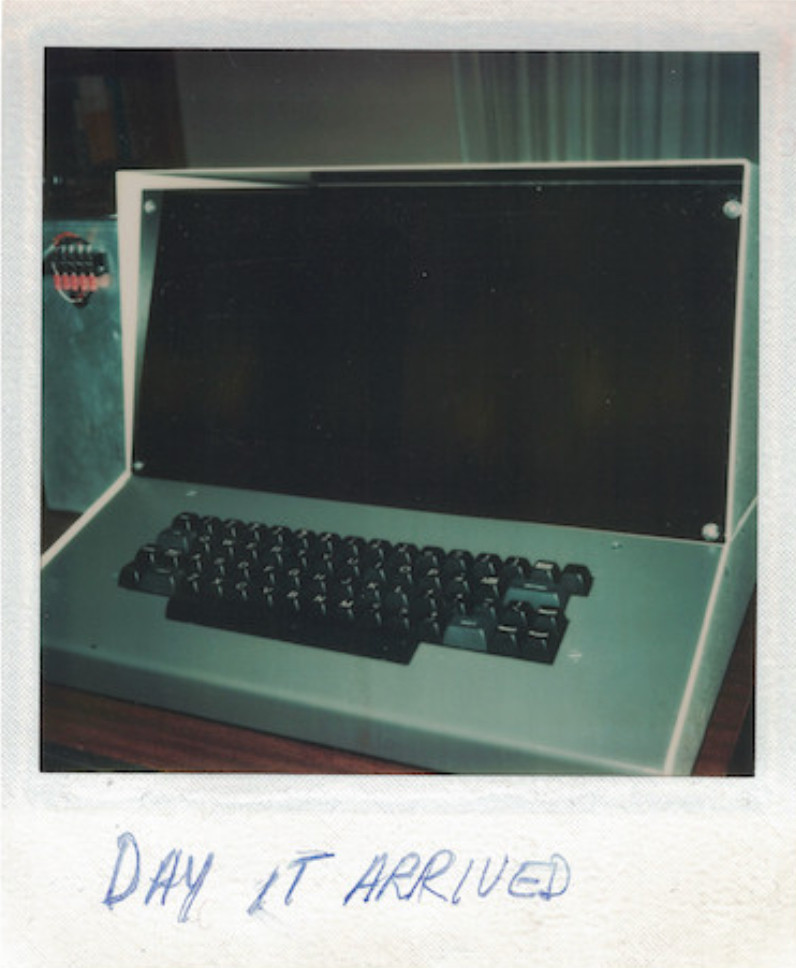

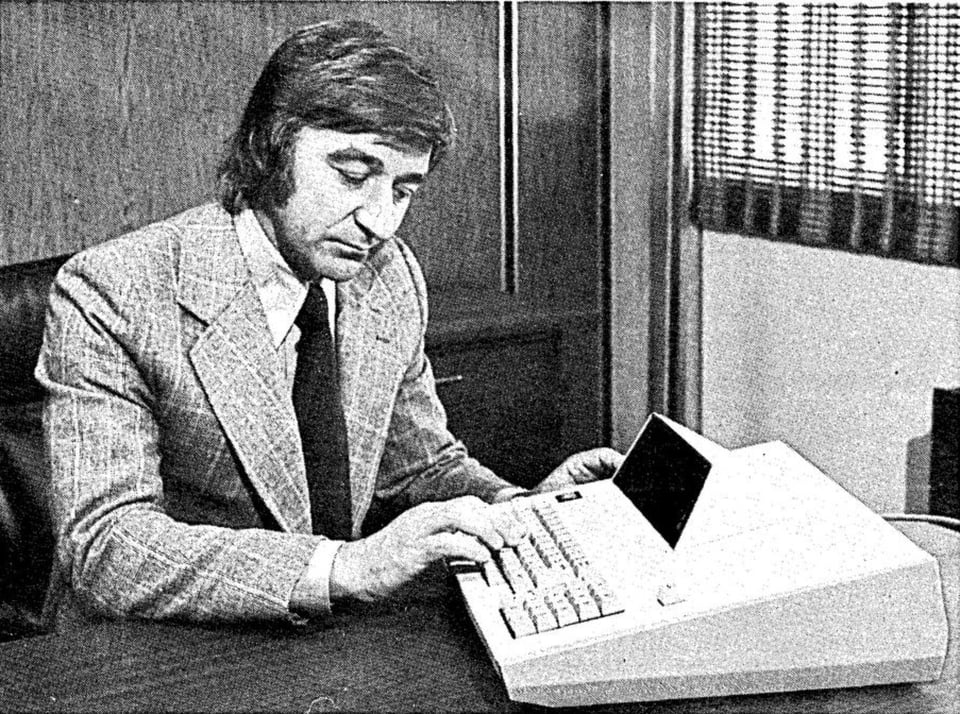

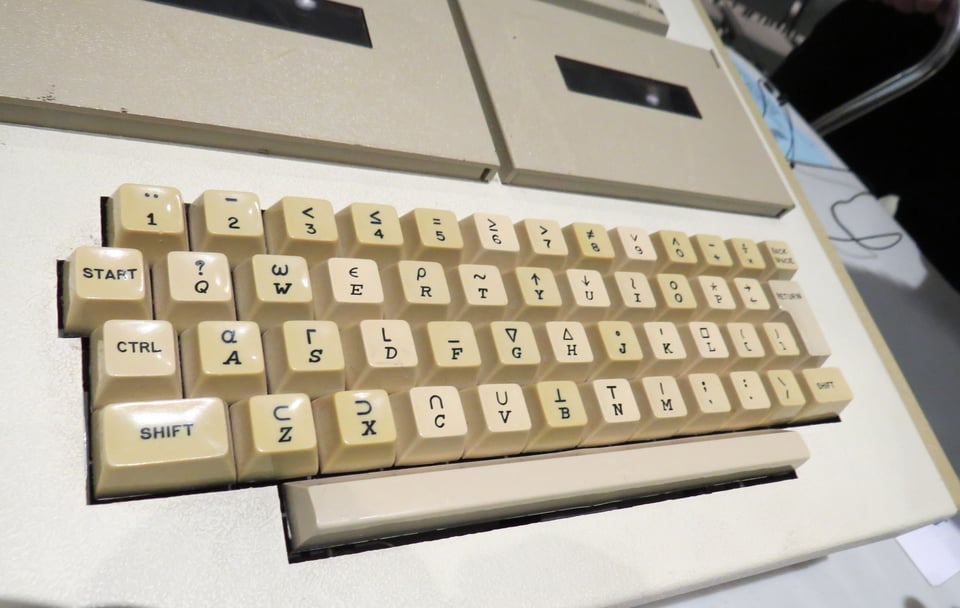

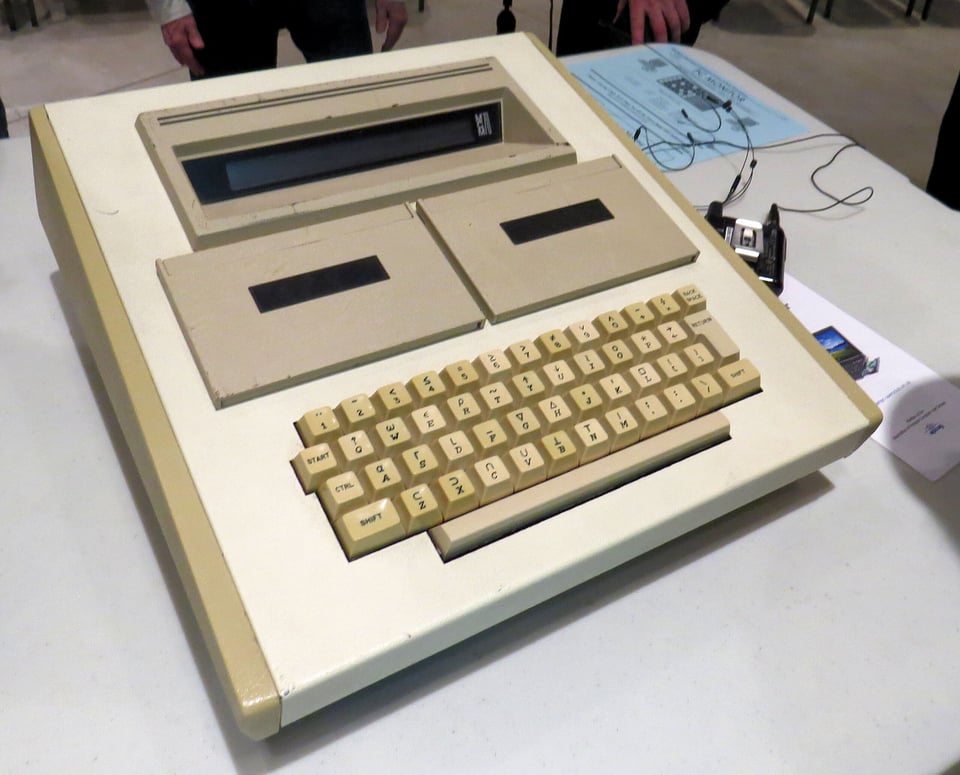

While André Truong and François Gernelle were building the Micral outside Paris, another basement was birthing another serious microcomputer, this time in Canada. Mers Kutt was a mathematician and inventor originally from Winnipeg. His flawlessly-named company, Micro Computer Machines, built a desktop system dubbed the MCM/70 while working out of engineer José Laraya’s cellar in Kingston, just outside of Toronto. The MCM/70 was a fascinating entry into the computing market, if only because of the approach it took to how you might use such a device. The MCM/70 looked like a sort of overgrown calculator with twin cassette decks in between the keyboard part and the single-line electronic display. Notably, the machine was built to work with the APL programming language, an unusual, expressively mathematical language that was symbolic in its grammar: you needed a specially labeled keyboard with the APL symbols to work in the language, and the MCM/70 incorporated one, its layout modeled after the IBM 2741 terminal:

On seeing an early demo of the computer’s capabilities, Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore, founders of Intel, were charmed by a neat little horse-racing game—a novel use of that single-line glowing orange text display, and one of the more lighthearted applications their 8008 had been used for by that point. But the machine could perform real work, and Intel “didn’t believe that this little chip they were producing could do this much,” remembered Kutt.

The MCM/70 launched in 1974, at a cost of nearly $10,000 for the more popular model, with twin cassette decks and up to 8KB of memory. Like Daniel Alroy’s Q1, the customers for the MCM/70 were companies and government institutions. Less of a business machine by nature, the MCM/70 was ideal for the simulation and mathematical work that the APL programming language was good at.

The cassettes, although sharing a physical form factor with standard compact audio cassettes, stored data not as audio signals but directly as digital signals. This allowed each tape to store up to 102KB, and it was also used by the MCM/70 as virtual memory: The computer could offload live data that wouldn’t fit in the 8008’s compact address space onto the tapes. Despite the visual similarities, this was a very different use of cassette storage—and required a much more expensive set of hardware technologies—than was seen in later hobby microcomputer cassette storage, or what Sphere used.

Founder Mers Kutt left the company in 1974, and MCM was blindsided by IBM’s introduction of its own portable APL-driven computer system, which left MCM scrambling. Somehow this tiny operation had earned direct competition from the biggest computer company in history.

In all, the company sold hundreds of units, but found themselves increasingly on the wrong side of computing with APL, as microcomputers became more generalist machines.

SCELBI

Nat Wadsworth started designing a computer in early 1973. Wadsworth, a high school dropout who had joined the Navy and then gone to University of Connecticut for a degree in Electrical Engineering, was a real computer enthusiast. The kind of enthusiast who would purchase his own PDP-8 minicomputer and Teletype machine—an enormous financial outlay on a professional machine that was certainly not designed or sold for personal, individual ownership.

It was that idiosyncratic inclination that led to the idea Wadsworth was pursuing: the opportunity for other engineers to have a small personal computer system of their own to work with. Fired up after attending an Intel seminar on their 8008 microprocessor, he thought that these chips could bring general purpose computing out of the labs and corporate accounting departments, and onto the engineering bench.

His employer at the time was uninterested in the small chips. So Wadsworth and his colleague Bob Findley struck out on their own, forming SCELBI Computer Consulting, and completing the design for what became the SCELBI 8H. SCELBI stood for SCience-ELectronics-BIology (and was pronounced “sell-bee”). Their computer debuted in the spring of 1974.

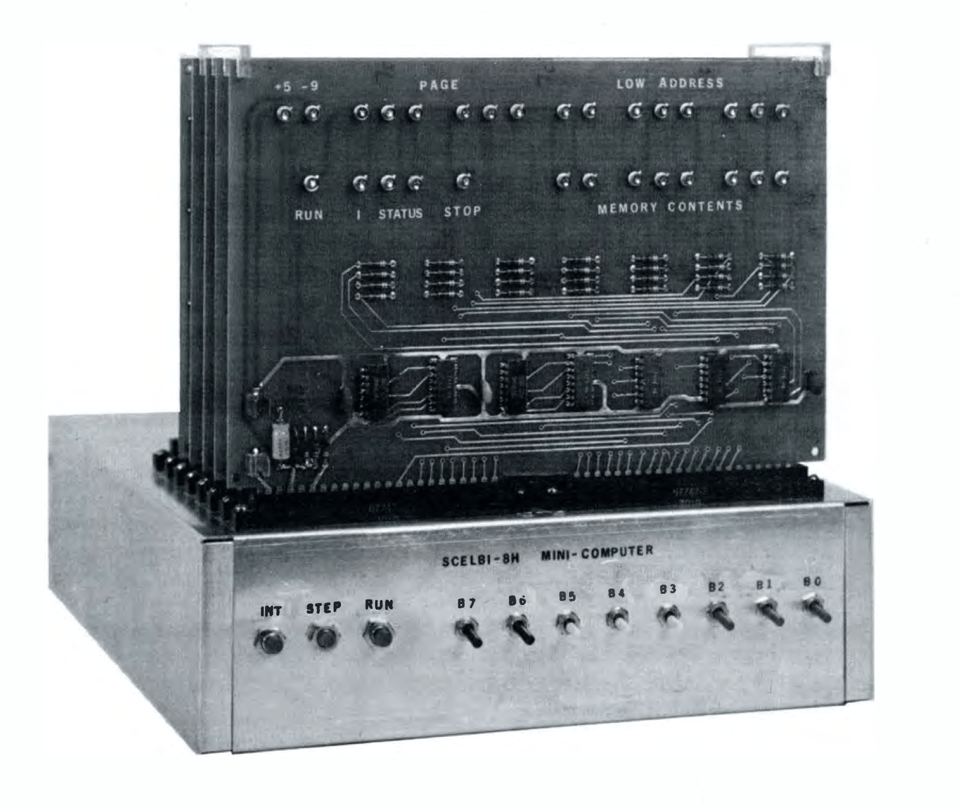

The SCELBI 8H looked like it belonged in a lab: a small aluminum base held a rack of exposed vertical circuit boards. The frontmost board acted as the “front panel” for the computer, with a series of LED indicator lights as the only “output” from the machine. Corresponding toggle switches to provide input and control were mounted below, on the base.

Wadsworth and Findley advertised first in QST, a magazine for amateur (ham) radio enthusiasts, describing their product as “The totally new and the very first mini-computer designed for the electronic/computer hobbyist!” The suggested uses of such a system were: testing TTL integrated circuits; sorting and compiling scientific data; operating as a “sophisticated electronic calculator;” and acting as control station for the physically handicapped to actuate various helpful devices. Two applications specific to amateur radio were suggested: translating typed text into morse code, and controlling a radio repeater. All such applications would require the user to craft appropriate software and hardware interfaces, of course.

SCELBI offered the computers pre-assembled, or as kits. Build-it-yourself kits were a common way of constructing electronic devices in the middle decades of the twentieth century, and the practice bled over into early home computing: the assembly and testing of units like the SCELBI was manual and labor intensive, even at the “factory,” so a customer could save some money by purchasing a kit of parts and assembly instructions, boxed up with schematics and other helpful diagrams.

Wadsworth was a prolific writer, and all of SCELBI’s printed documentation—in his distinctive Teletypewritten all-caps—was meticulous and comprehensive. A customer would require a soldering iron, other basic bench tools, and a lot of patience. The process of constructing and verifying a SCELBI kit would take “typically less than 20 hours,” reassured the sales literature, assuming you were a “qualified assembler.” Many early computer purchasers were engineers, and the experience of building the computer was itself pleasurable and educational.

The “starter” SCELBI 8H system, which included just the five core boards and only 256 bytes of RAM memory cost $440 as a kit ($510 assembled and tested). This was a remarkably low entry price for something that could be called a general-purpose computer. But this bundle did not include the chassis base or card slots, or anything else: the customer had to rig up their own quite complicated set of interconnections and switches as well as a DC power supply for the system. The limited memory—256 bytes, or just a quarter of a kilobyte—was enough to let a user play around with the system and understand how it worked, but not enough to do much of use. A complete SCELBI 8H system, with the aluminum chassis, power supply, and an expanded kilobyte (1024 bytes) of memory was still under $1000— $795 in kit form, $950 pre-assembled.

Unlike most other early microcomputers, SCELBI did not expect the user to have a Teletype terminal interface for user input and output. In fact, at its initial launch, it offered no “console” connectivity at all. But later in 1974, SCELBI offered a direct keyboard interface and video output box, which was designed, uniquely, to produce text on an oscilloscope screen. Oscilloscopes are workbench devices used to examine electrical signals in order to understand and debug circuitry. The pattern of the signal is shown on a small video screen, which were built with small cathode-ray tube (CRT) screens, like a miniature purpose-built television monitor. Assuming many of the engineer customers would already own such a device, Bob Findley devised a clever bit of electronics that would produce readable text on the screen of an oscilloscope. This was a very neat idea but too clever to be broadly useful, and only about four such interfaces ever sold. A serial interface for standard terminal interfaces was eventually available.

For those who did not have a teletypewriter with its paper punch tape for data storage, SCELBI offered an audio cassette interface box, something that would be common on microcomputers until the advent of inexpensive floppy disk drives at the end of the decade. Cassette tapes were cheap—you could buy them at your local Radio Shack along with an inexpensive recorder—and data would be stored, very slowly, as audio tones on the tape. Unfortunately the user still needed to “toggle in” a small bootloader program on the front panel that could start the tape load process, and that alone could take ten minutes for an experienced toggler (adding a bootstrap EPROM could help, but that was its own project).

The SCELBI systems were lauded by the few who purchased them, but it was ultimately a system only an engineer could love, or even use. The primary switch-based control of the computer was counterintuitive and excruciatingly slow, and the multifarious interconnections between parts of the system and any external devices were bespoke and complicated. You needed a sophisticated understanding of electronics to do much at all with a SCELBI computer. The company sold perhaps a couple hundred units across both kits and assembled computers, including both the original 8H and the upgraded 8B.

Nat Wadsworth suffered not one but two heart attacks during the startup phases of the company. He was only 29, and an open heart surgery in the midst of the first deluge of interest in the computer in mid-1974 prevented SCELBI from fully capitalizing on the market. Wadsworth leaned into writing and the SCELBI name became much better known as a technical publisher in the subsequent years.

Nonetheless, Wadsworth’s invention is notable for being the first microcomputer system marketed to an individual who might use it at home, and not coincidentally, was an early salvo in a flood of computer hobbyist kits to come.

Speaking of kits, the next entry in this series will look at another important 8008 kit and then the most consequential microcomputer kit, the one that finally found a real market.

But until then! Remember, these are cutting room floor stories that didn’t make the cut for my Sphere book, Go Computer Now! That book is currently raising funds for printing via Kickstarter. If you like this kind of writing and haven’t taken a look, please do! The book is like this article, but mostly about Sphere, and substantially more detailed. :-)

Best,

Ben Z

Sources:

Zbigniew Stachniak, Inventing the PC: The MCM/70 Story (McGill-Queens University Press, 2011).

Stachniak, “The Making of the MCM/70 Microcomputer,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, April–June 2003.

Fantastic MCM/70 photos and info on Santo Nucifora’s site here.

The compact but excellent SCELBI Computer Museum at https://www.scelbi.com

Communication with Mike Willegal, SCELBI expert and author of a forthcoming book on this computer that he’s been working on for years. Can’t wait!