Road to Sphere #2: Q1 and Micral

Brief histories of the Q1 computer from Long Island, New York, and the Micral computer from France!

Last time we looked at a couple prehistoric “PCs” from the turn of the 1970s; today we’re going to explore ideas that emerged in the subsequent couple years, in New York and in France. These are Intel 8008 computers, and though neither set the world on fire, they were interesting and early experiments along the path to personal computing. This continues a short series based on material that was cut from my upcoming book, “Go Computer Now!”, about the Sphere microcomputer from Utah.

First up is a very ambitious idea that came from Long Island.

Q1

Daniel Alroy started Q1 Corporation on something of a dare. Alroy was griping to a stockbroker acquaintance that a Datapoint terminal had the wrong idea, so the broker prodded Alroy to do better himself, teasing that he’d seed such a venture. In Alroy’s telling, it was at his prompting that Robert Noyce, the legendary co-founder of Intel (and Fairchild Semiconductor before that), restarted the stalled 8008 project after Datapoint went off on their own. Alroy suggested to Noyce that he might be the inaugural customer.

His Q1 Corporation of Farmingdale, New York, delivered what was probably the first general-purpose microcomputer in December of 1972. It did indeed use the new Intel 8008 chip, and appeared about a year and a half after the first Datapoints showed up at Pillsbury chicken farms. It, too, was a stylish business machine with a commensurately exorbitant price tag.

Daniel Alroy was a mind-brain academic by both training and temperament. It was only natural that he began by conceptualizing, and Alroy was working from two key insights. The first was his belief that “there would be a continued, rapid increase in the number of transistors per unit area and a corresponding decline in the cost per transistor.” He thus “concluded that a basic new trend would emerge, of computing at the point-of-use.” As in, full computers at the office desk as opposed to in a special room. His other conviction was more philosophical: computers had been hobbled by their dedication to specific tasks, and since a microprocessor could be used to do anything, so should a computer be liberated from the shackles of specificity!

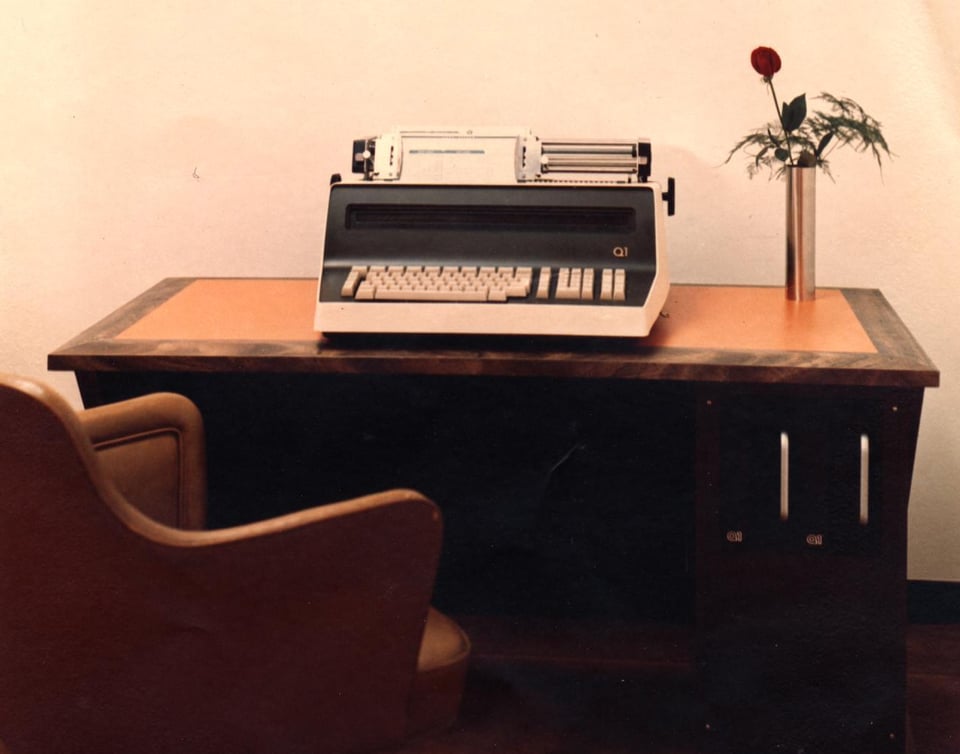

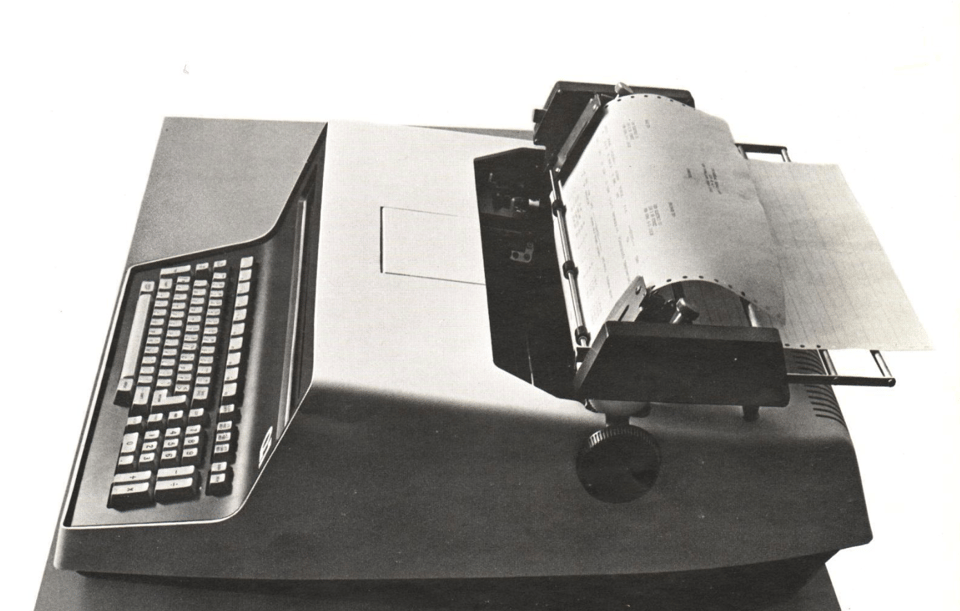

The Q1 was designed to replace a typewriter on a professional’s desk, and here the resemblance was strong enough for a double-take: paper emerged from the top of the machine because it incorporated a built-in printer, and the side of the unit had a big roller knob to feed it. If you didn’t notice the single-line electronic display above the keyboard, you would have assumed it was a typewriter.

But the Q1 was a kind of microcomputer, intended for business use, and the 80-character readout was its primary display. It could be programmed in the Intel machine language, or in IBM’s high-level applications programming language, PL/I. This latter system was a key marketing point for Q1, and the company described PL/I as a 90% time saver for building business applications. (Alroy and his team considered BASIC to be “inadequate,” and COBOL required too much computing power to run well on the limited 8008.)

Although later versions of the Q1 would support 8” floppy disks, the initial version used special magnetic cards that slid into the side of the computer. Each card could hold a total of 10 kilobytes of program or data. Alroy’s system was described by the press as a “desk-top minicomputer” and it cost about $20,000, out of reach of all but very serious corporate customers. (That’s about $150,000 in 2025 dollars.)

Alroy’s company sold the machine to credit unions, government agencies, and eventually, NASA. The first customer was Litton Industries, a huge multinational conglomerate.

The Q1 computer may have been suitable for general purpose use, but at the time, business applications were the extent of what could be imagined (and afforded). Daniel Alroy’s machine evolved quickly—including a notably capable 1974 revision with a multi-line screen based on the bleeding-edge Intel 8080—but remained the province of well-heeled institutions; by the end of the 1970s, Alroy himself returned to academia. Yet his founding observations were prescient: computing was moving into smaller, self-contained units which would be able to perform all kinds of different tasks at the request of the user.

Micral

Around the time the first Q1 was being delivered on Long Island, a handful of men 3,600 miles away were hunkered down in a cold cellar in the Parisian suburb of Châtenay-Malabry. The team was led by engineer François Gernelle, and the men were on a deadline, working eighteen-hour days in dark winter.

The goal in that basement was to build a microprocessor-based computer of their own, under the banner of the small electronics firm R2E. The first customer, to whom they’d committed a delivery date of December 30, 1972, was the French National Institute of Agronomic Research (INRA).

The Institute had a measurement headache they needed to solve. Evapotranspiration is net loss of water to the atmosphere from earth and plants, and understanding its mechanics is key to the efficient watering of crops. INRA needed a system to take automatic temperature and humidity measurements at different heights above the ground, and run calculations on them. A Digital Equipment PDP-8 minicomputer system, which could have been programmed to do this work, was prohibitively expensive. Gernelle proposed that his firm could solve the problem using one of the new American microprocessors from Intel for half the price of a PDP-8. INRA agreed to a contract, and Gernelle’s team launched into a six-month frenzy of effort.

R2E, an abbreviation of “Réalisations Études Électroniques” (roughly, Electronic Creations and Studies) was founded by engineer André Truong in 1971, and had to that point focused on contracts in medical and industrial devices. This was something different and more ambitious, which is why Truong, Gernelle, and several others spent that winter in the basement, surrounded by the urgent clatter of Teletype machines.

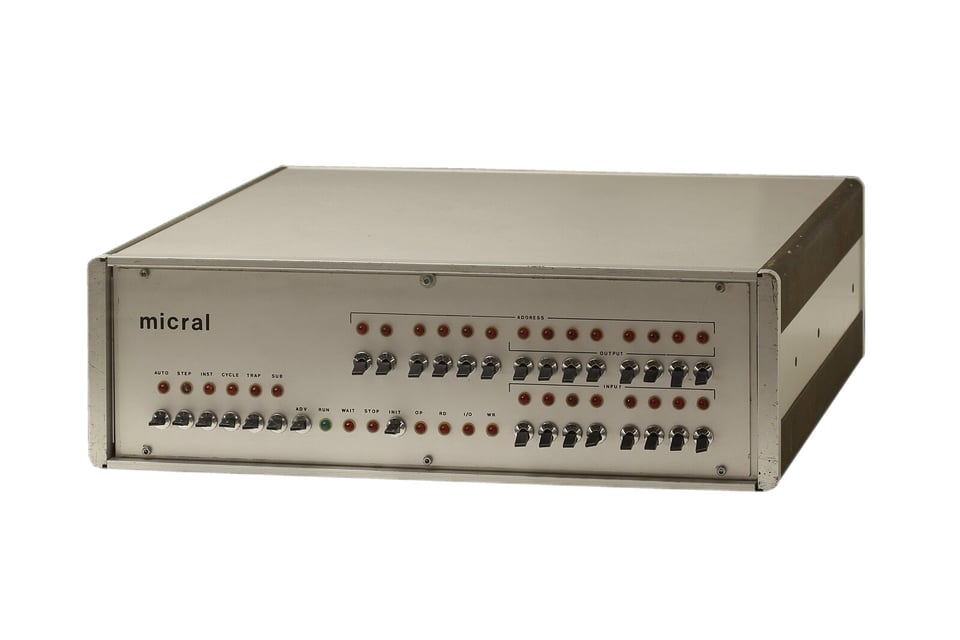

Their creation was a durable metallic box, full of manually wire-wrapped circuit boards. At its heart was an Intel 8008, and on the uncluttered front panel were a handful of switches and a lamp or two. It looked something like a home-made stereo amplifier, which hid its considered hardware structure. The R2E team didn’t quite make the deadline, but delivered their system and attendant software to INRA the middle of January of 1973.

So far, this sounds like an example of the Intel 8008 microprocessor being used more or less as Intel imagined it might be used: for industrial process control. The cost savings idea that led Gernelle to pitch INRA on a microprocessor system was in line with Intel’s early marketing of their 8008 system.

But the machine they had built, inspired by minicomputers, could do more than evapotranspiration math, and Truong had bigger ambitions. R2E commercialized the creation, naming it “Micral” and launching in April of 1973 at a price of about $2000. Micral was French slang for “small.”

The Micral was constructed as a general purpose computer system: it was intended to be programmed to do varying tasks. In this way it was closer in spirit to a DEC PDP machine (or the Q1) than to a bespoke microcontroller. Unlike the Q1, however, the Micral was not meant to sit on a worker’s desk, and was not “self-contained”. The metal cabinet was rugged, so that it could be deployed in field installations. The final unit’s front panel featured 30 small black paddle switches and 35 LED lights, a small-scale echo of a minicomputer control unit, allowing memory and data to be examined and altered directly.

The Micral N (as it was eventually retitled to distinguish the original computer from later revisions) was the first of a particular strain of early microcomputer: a box, expandable with various boards, and a front panel festooned with controls. The Micral’s spiritual ancestors were minicomputers like the DEC systems. So it was only natural that the “computer” was a box that was entirely separate from a terminal that was used to talk to it. The box itself offered only the most painstaking front panel controls.

The R2E team also included Alain Lacomb, Jean-Claude Beckmann, and Maurice Benchétrit. They built up all the structure and software themselves. Gernelle remembers that “in 1972, there was no software from Intel: no debugger, no monitor firmware, no assembler, nothing.”

André Truong, as co-owner of the company and its public face, tended to receive the credit for this early entry in microcomputing — being named “father of the personal computer,” inventor of the microcomputer, or creator of the Micral by press and industry. That didn’t sit well with Gernelle, who thought himself the actual creator and Truong more of its business champion. Gernelle went to court in Versailles to lay claim to the title of “inventor of the microcomputer,” and eventually succeeded—for whatever that was worth.

Truong and R2E marketed the Micral for process-control uses. Some were probably sold to individuals, but most were used in industrial applications like agriculture, banking, and operating tollbooths. By the end of 1973 some 500 units had been sold, only in France. More were shipped in the following years, but R2E was unable to break into the crucial American market, and Truong sold out in 1979 to French computer manufacturer Bull.

…

Next time, we’ll look at a desktop mathematical wizard from Toronto, and start talking about kit computers.

You can always reach me at bzotto@gmail.com. Information about my forthcoming Sphere book is at https://gocomputernow.com. All text is copyrighted by Ben Zotto. Thanks for reading.

Ben Z

Sources:

Abdi, Nidam. “François Gernelle, 54 ans, est le père du premier micro-ordinateur, mis au point en France en 1973.” Libération, April 9, 1999.

Alroy, Daniel. “The Advent of the Microcomputer Era: An Eyewitness Account.” https://web.archive.org/web/20180826164617/http://www.philon.net:80/technology

Computerworld. “Minicomputer Allows PL/I Programming,” January 31, 1973.

Datapro Research Corporation. All About Small Business Computers. October 1977.

Gernelle, François. “La naissance du premier micro-ordinateur: Le Micral N.” Deuxième Colloque sur l'Histoire de l'Informatique en France, April, 1990.

Gernelle, François. “Communication sur les choix architecturaux et technologiques qui ont présidé à la conception du «Micral» Premier micro-ordinateur au monde.” Actes du 5e Colloque sur l'histoire de l'informatique, April, 1998.

Kastrup, Bernardo (aka The Byte Attic). Q1 Materials archive. https://github.com/TheByteAttic/Q1

Simpson, Roderick. “A Talk with the Father of Computing.” Wired, September 15, 1997.

Six, Nicholas. “Fifty years ago in France, Micral N, the first commercial microcomputer in the world was born.” Le Monde, January 16, 2023.

Smets, Richard M. “Microcomputer Systems for General-Purpose Computation.” 1975 IEEE Intercon Conference Record, IEEE, 1975.

If you’re interested in the Q1, Morten Christensen is working on a Q1/Lite emulator—a later evolution of this fascinating machine.